I spent some of the greatest years of my life professing. And this was a paid gig at a reputable institution, not me standing on some bustling street corner in a greasy suit trying to rile excitement about communism, UFOs, or Jesus. And even though I have a letter from the Dean of my department addressing me as Professor Mandel, my students called me Jordan, and in the wise and reconjucated words of the Backstreet Boys, I wanted it that way.

In 900 different ways, the formality and etiquette that made the world turn for hundreds of years has fallen into the ditch, been acid-rained upon, and buried by a few dense layers of sediment. Which side of the plate does the fork go on? do you end sentences with prepositions; begin them with capitals? And most inconceivably – do you call an illustrious Master of Popular Music and Culture by his first name??

The names we use to address people in our lives (or who aren’t at all in our lives, but we want to suggest are in our lives) reveal a whole bunch of interesting social phenomena that Alvin our Alien Anthropologist would find rather strange, if we earthlings weren’t strange enough already.

"What's in a name? That which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet."-Juliet, of Romeo and Juliet notoriety

Maybe Juliet was onto something when talking about a rose or her beloved Romeo from that good-for-nothing Montague clan, but when it comes to the names we use to address people around us, I’m going hard against Shakespeare and Juliet and saying there is most definitely something in a name.

When my students called me Jordan instead of Professor Mandel, I was intentionally decreasing the distance between us. Most of what angered me in my own miseducation were teachers who used their half-decade of slaving away on a PhD as a moat between them and their students. Sure, respect is important, and I was sure to inculcate that in my students on the first day by delivering a Stone Cold Stunner to the last student in the door.

In the case of my class, my students had direct contact with me; we occupied the same room for a few hours each week, they heard my voice, and when they asked questions I’d answer them. Unless they asked why I’d Stone Cold Stunner’d the late kid, at which point I’d glare at them, crack open a can of beer and snarl, Cuz Stone Cold Said So. In my biggest classes there were still fewer than 100 students, and even though we might’ve been defying one norm of students calling me Professor Mandel, they had direct interactions with me so it wasn’t all that unusual for them to use my first name.

Now, let’s blow this scenario out to the grand circus we call the world today, where we add six more zeroes and have 100 million people calling a rapper by his first name who’s in a well-publicized feud with another rapper with only one name.

Let’s be clear: Drake is a brand name. Aubrey Graham has only ever released albums with Drake as the artist name (it’s his middle name, but still). It sounds a little bit badder-ass than “Aubrey”, which probably goes a long way once he finds himself in a battle with Compton-raised Kendrick Lamar Duckworth, whose full name seems to steadily lose badassery as we move through it.

Now I don’t care about us using peoples’ birth names if they have well-established stage names. The stage name ends up being the public name, and this gets to the crux of this post: when do we use a first name, and when do we use a last? Or maybe more interestingly, why do we use a first name, and why do we use a last?

When we know a person well, we tend to use their first name, at least in Western cultures. If you worked as an executive at Apple in 2006 and had regular meetings with your boss, you’d be very likely to call him Steve. I call my boss by his first name. When I worked for Shopify I called the CEO of the company by his first name. I realize this is already a massive leap forward in casualness from industrial-revolution employee relations, but hey. The etiquette is in the ditch.

We probably know someone who refers to their spouse or family members by their first name in conversation, even if you’ve never met the person. Despite being jarring, it indicates familiarity between the person speaking, and the person to whom they’re referring. So much familiarity in fact, that they don’t even bother qualifying who the person is.

Using first names of people in the corporate world can be especially weird, once you’re talking to people outside the company. This came to a head a few years ago when a Facebook marketing executive was speaking on a panel inside Shopify and kept referring to “our founder, Mark”. It took me half the conversation to figure out who the hell this guy was talking about. (And then the other half of the conversation – and all these intervening years – to shake off the gross feeling from that perverse description that indicated any degree of closeness to “Mark”. His name is obviously Zuckerberg. I presume his sisters and parents even call him Zuckerberg.)

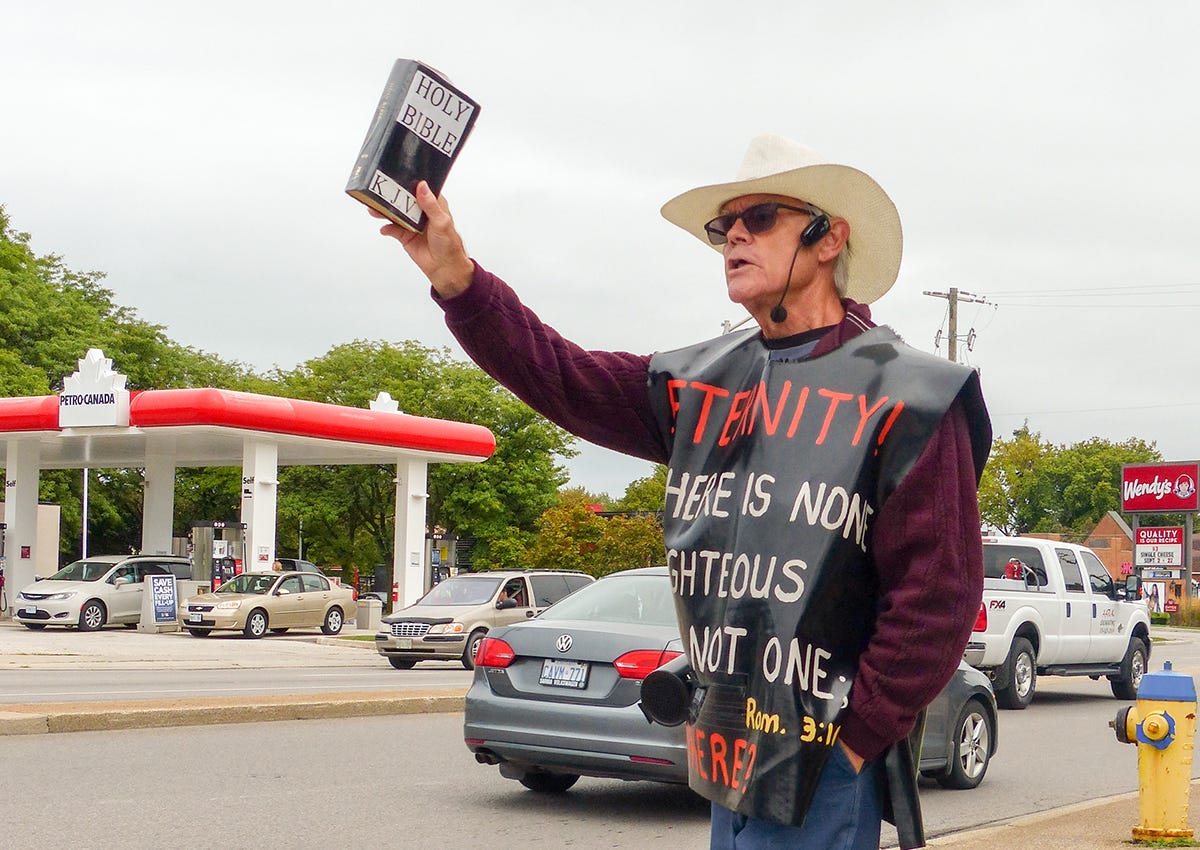

I’m going to state my opinion very clearly: if you’ve never met a person, you have no business calling them by their first name, period. Jesus… we’ll let that one slide. But maybe Jesus is the strongest point I can find. The Jewish god’s name was considered so holy that only the high priest could say it, and only on the holiest day of the year. That’s some serious distance. But Jesus is far more accessible. He was knowable in his time, and from what I hear – at least from the guy professing through a megaphone downtown – he’s knowable even today. I can write his name in this heretical paragraph and not fear being struck down by a lightning bolt.

When we use someone’s first name, we’re generally indicating a sense of closeness. And this is why the cynical part of me bristles every time I hear people refer to Steve, Elon, Leonardo, Raphael, Michelangelo, and Donatello. Unless you’re referring to the Ninja Turtles, use their surnames. And especially if you’re talking about a tech CEO that you’ve never met.

Using a celebrity’s first name garners a parasocial relationship, as Donald Horton and Richard Wohl described in 1956. Media personalities deliberately create an illusion of closeness with their audiences, which creates a lopsided relationship. Hundreds of millions of people including my own children believe they know Taylor, and she might have a bit of a larger network than your typical Pennsylvanian, but not by that much. She doesn’t know my kids.

We typically say a person’s full name if they’re really distant and someone unknown. We might shorten it to their last name if they’re distant and somewhat known. And in these freakish cases, we might switch to their first name if the people around us seem to be doing that, and we want to signal that we’re part of the in-crowd.

But be careful. If you walked past this person in the street and said hi, would they recognize you? Would they be calling you by your first name? Or is this a stranger who you’ve let sneak into your inner circle of familiarity and feel a greater sense of kinship toward, because you refer to them the same way as you would a friend or sibling (of course, unless you’re the CEO of Facebook and even your family calls you by your last name)?

Consider how close the person actually is – not how close you want them to be – and choose the name accordingly. You might lose a few fan club membership cards along the way, but you could avoid getting stunner’d by not calling Mr. Austin Steve if you happen across him in the middle of the street.

And if he tries to bridge some familiarity by telling you to call him Stone Cold, give him the middle finger, crack a can of beer and tell him you’re not gonna do that… because Professor Mandel said so.

This article reminded me what I like about 99PI - you brought to light what is gradual shift in society which pretends there’s familiarity and connection when there isn’t - which can create a inauthentic sense of intimacy

Absolutely love this post, on so many levels.